A Precarious Balance: Home Space - Pari

(Fairy)Space

- Other Forces of Nature

As part of our expedition to Hunza The Pak Khawateen Painting Club trekked

across glaciers, mountains and streams. We photographed, documented,

wrote, ate and rested in a unique environment that was unlike our own. The

topography, rituals and social organization in Hunza- in short landscapes

of everyday life- were defined in relation to different experiences of

space. As I acclimatized and adapted, not only did it become apparent that

Hunza retained a strong oral culture of story-telling but the

entanglements between culture, tradition and environment were unique, to

say the least. Lived experiences and memory narrated through cultures of

storytelling could transform natural phenomenon, functions and entire

landscapes into something magical or extraordinary. I became increasingly

interested in place-lore, a term used to describe stories that people tell

about physical and natural surroundings familiar to them. Sometimes the

place or setting being spoken about in say a folklore would be present in

the actual landscape itself. The physical environment itself would become

a catalyst for the production and interpretation of meaning i.e natural

phenomenon were explained through fantastical vernacular interpretations.

At other times ecological concerns were merged with morality and piety;

folk stories were supposed to serve as a mode of admonishment in response

to ecological imbalance created by human activity/human

greed. Since the central concern of the expedition was tied to

environmental risks and catastrophes that do not recognize geographic

boundaries established by nation-states, storytelling, it began to seem,

could traverse these limitations and elevate the narration to encompass

concerns about ecology, harmony and balance in nature. Certain cultural

and ritual practices involving the natural environment in Hunza began to

emerge almost as acts of transgression vis-à-vis state

ideologies that craft and legitimize narratives around geopolitical pasts;

after all it is nation-building that ensures that boundaries are

established and borders are maintained. Were these cultural traditions and

practices indicative of remnants of an agrarian and animist way of life

that was either co-existing or contesting space with the narratives of

salvation religions(Islam, Christianity

etc.)? The existence of beings other than divs and

churails which are either male or female in storytelling was also

fascinating. One of these beings was called a pari. I speak Urdu and

coming from the plains or down se (from down

there) - as I sometimes had to introduce myself in

colloquial terms- the word pari meant

"fairy" and implied a female gender.

However, Hunzakut say that "the pari appear to be the

embodiment of natural forces, displaying the life-giving and

life-threatening attributes of the mountains. Hunzakut say that the pari

jealously guard their domain against human encroachment. This is why the

Hunzakut traditionally regarded the up- land pastures and the mountains

beyond as sacred places, the hallowed domain of the pari...these

supernatural beings are offended by the presence of women

(believed to be impure because of their menstrual periods)and

cattle (from down there)

."(i)

The pari then can be considered akin to capricious, animist spirits that

eschew gender and maintain order in the spirit world that pertains to

nature. Interestingly I did document stories where the pari was given

certain human qualities indicating their malleable identity that was

informed by context and environment. To elaborate on how I then

interpreted the term pari and incorporated it into my title I turn to

James C. Scott and his book "The Art of Not Being

Governed." James C. Scott considered the hill-people of

zomia (a geographic region that is located at an altitude

which is above three hundred meters and encompasses Southeast Asia, East

Asia, South Asia) as being evasive of state-making

ideologies.(ii) (iii) The people of Hunza with their

animistic rituals and oral folklore carry similar tendencies. The flexible

use of the word pari also implies resistance to fixed identities informed

and constructed by nationalist ideologies.

To me "Pari-space" therefore represents

an imaginary refuge much like zomia, it is transformative and in flux. It

is, of course cultural heritage but perhaps also an intangible

manifestation of what might now in modern times be considered,

transgressive activities, that nevertheless still inform the cultural

memory and life of the people of Hunza. Unfortunately, climate change and

the frequency of environmental disasters such as

(GLOFS) threaten this symbiotic

relationship between place-lore, land and people.

The first half of this essay examines, cultural rituals, snippets of

interviews and conversations with residents of Hunza which I felt, carry a

consciousness of environment, ecology and history. Could some of their

stories be considered place-lore that is integral to understanding and

valuing the endangered natural resources of Hunza? If their rituals carry

the imprint of older animist cultures then will global warming affect

everyday life and the transmission of this knowledge in Hunza? In the

second half of my essay I discuss the works of two artists, one from Hunza

and one from the princely state of Nagar. Both artists draw on the

cultural memory of Hunza-Nagar in some capacity, they use

environment-related or culture-related stories to generate interest about

transnational identity, nature protection and cultural heritage. Are South

Asian artists acknowledging these histories and weaving them into their

artistic practice with an awareness of place-lore and ecology?

Mujeeb is a graduate of the National College of Arts, Lahore. He currently

manages the Altit Hunza Music School located inside the Royal gardens of

Altit Fort. We were able to witness the shamanistic practice of Bitan

owing to the efforts of Mujeeb and his friends who located a practicing

shaman and accompanied us to the ritual. Bitan was described to us as an

experience where the shaman would serve as a seer, prophesying and

describing our futures. Broadly speaking shamanism is described as

religious functionaries who draw on the powers in the natural world,

including the power of animals, and who mediate usually in an altered

state of consciousness, between the world of the living and the world of

the spirits- including the spirits of the dead. (iv)

In this particular experience with a shaman there was no visible evidence

of the use of the power of animals. We were seated in a room and watched

as the shaman lit and inhaled the smoke of juniper tree branches before

going into a curious trance-like state. He intoned mostly without pause in

an old dialect of Shina which was, oddly enough, intermingled with

recitations in Arabic. Mujeeb explained that Shina was also called

" the language of paris" and it was the

paris that were relaying all this knowledge to the Shaman. Any attempt I

made to ask whether that meant female or fairies was met with a matter of

fact reply: "They are just paris." (vi)

Sajjad Roy, a practicing artist originally from Hunza explained the

practice of Bitan, as a performative act that was conducted outdoors and

integrated natural landscape and animals into ritual. He elaborated that

once upon a time it was shamans who could predict when the crop was to be

harvested and when the ceremony of Ginani was to commence. Roy recounted

the incident of a famous shaman "who went into a mountain

with an empty thaali. When he came running out of the same mountain the

thaali contained grains of wheat, a ball of kneaded dough made from wheat

and a prepared flatbread. The shaman then announced that Ginanai could

begin." (ix)

Roy's other recollections of Bitan are more visceral.

"The Shaman performs in a crowd. He drinks the blood

from a goat 's severed head as if using it as a

vessel/container. To us it is seems grotesque but to the

Shaman it feels like he is drinking milk that comes from the horn of rams

brought by the paris themselves. " (x)

Roy too, parried the question of gender and any description of this

supernatural being.

Asad Bhai, as he liked to be called, was the caretaker of our rest

houses

in Gulkin and Aliabad. He often attempted to regale us with late

night/after dinner stories about supernatural beings. Many of my queries

were met with enthusiasm, the prelude consisted of an elaborate

narration

of geographic location, a description of natural topography followed by

the actual answer to my question. However, on the question of paris,

gender and description Asad Bhai was hesitant and said he had no

definite

answer. The importance of harvest, mountains and even juniper in

conversations with Roy and Mujeeb signify the relationship of place-lore

to symbols that represent the potent powers of nature and geography.

Paris

emerge as genderless beings in these accounts. Roy recalled another

entity

with an ambiguous gender identity called dado-puppo when he relayed

that

"...there was a huge boulder near my house... In

winters

as a child I remember we would sit on that rock and eat traditional food

called mool. Since we sat and consumed the food on the rock it was as if

we were feeding the dado- puppo." (Fig. 1)

What is the dado-puppo exactly? I asked.

We could consider it the spirit of an elder nut not a jinn. Dado means

elder or old while puppo means old sage. (xi)

This was more than just a local, vernacular explanation for the

existence

of a rock. Roy ended by saying that the boulder should never be moved

because it had a spirit and that it consumed food just like humans.

Implicit in this place-lore was a warning and lesson: every rock and

boulder had a meaningful existence. Nature was being sustained by a

fragile balance. These world views appeared to be informed by cultures

and

religions such as Buddhism , Taoism/Daoism that had

travelled across the Silk Route hundreds of years ago and nourished the

cultural landscape of the region. Interestingly in another folklore

story

Roy went on to attribute other human qualities to supernatural beings as

well.

When we have sudden windstorms that last about 20-30 minutes and there

is

alot of sand, it tells us that the dado-pupo and pari are getting

married (they are mating and the sand is providing a

cover of modesty). (xii)

Asad Bhai, the caretaker of our resthouses at Aliabad and Gulkin

explained

the existence of ancient trees and boulders in Chatorkhund located in

the

westernmost part of Gilgit-Baltistan in the following words

There is a place in Ghizr called Chatorkhund where a famous Shah sahb

"he has passed away" known for his

intellect , piety and contribution to society...he gained fame for

capturing a div notorious for harassing villagers in the area...Shah

sahb

made him work, the div is known to have picked up huge boulders and

placed

them there near where Shah sahb ' s house was. The

boulders form a sort of wall. There are also huge trees near Shah sahb

' s house. It is said the Div picked them up from

another

area and planted them there. They still exist. The size, shape and age

of

those trees and boulders should tell you how ancient they are and that

it

was impossible for anyone except a div to have lifted those.

(xiii)

Such examples of place-lore contain many environmental signs, perhaps

they

not only help explain the occurrence of unique natural phenomenon such

as

a change in seasons, weather etc. but could also relay knowledge about a

sensory experience. These stories and practices could also suggest that

it

is the untamable and whimsical nature of the landscape that prompts

their

instinctive response; it highlights a more reciprocal relationship

between

man and nature. Abstract emotions such as shock, awe, wonder and mystery

are inscribed as a sort of subtext within these stories, they provide

clues about the emotional connection that inhabitants build with

landscape. While paris and their gender remains ambiguous, the oral

narratives by some of my other interviewees were charged with

descriptions

that ascribed gender, socially constructed relationships and even human

attributes to the natural environment.

Wazir Iman, a resident of Hunza who had been working closely with UNDP

on

disaster management of Glacier Lake Outburst Floods (GLOF)

delved into his experience of walking

on glaciers and noting the effects of climate change. He decried the

rapid

rate at which the sides of glaciers were atrophying and melting, leaving

behind rocks from moraine that would either block the path of

floodwaters

or come crashing down as landslides. (xiv) On being

asked about the GLOF that had occurred recently , just a few months

before

we arrived and how a hotel had been washed away in Kalam, Khyber

Pakhtunkhwa, Iman responded Woh uska haq tha, woh uska rasta tha

(xv) translated as " it was the right

of

the river, that path belonged to the river." This

particular line as well as many of Iman’s other descriptions of water,

paths and rivers expressed the kind of protective affinity or bond he

had

established with the natural environment: he had imbued it with human

qualities such as the ability to reason, decide and think. He was

willing

to speak up for the "rights" of water

as

if it was a living breathing being. Iman sympathized with the waters of

the GLOF as if they were a human entity of sorts stating that man had

made

the life of these melting waters difficult by blocking their way and

artificially attempting to control and restrict their path.

(xvi) He then poetically elaborated on how glaciers

are

in a constant state of parting and union. They recede every seven years

and grow back another seven years. It was described as a process of

yearning to meet and mate. Shishper and Batura glacier was male, Passu

was

female."Perhaps the meeting of their melting waters is

as

close as they can get to mating" (xvii) said Iman

eloquently. Such place-lore perhaps illustrates the more symbiotic

relationship between traditional communities and their environment,

"between tangible reality and the

storyworld." This creative impulse helps foster empathy

and engenders an

ecology of care where man gains the capacity to acknowledge the eco

system

as a living breathing entity. In this storyworld genders, relationships

and personalities are inscribed on the geography and natural

characteristics of the environment itself.

The storyworld can also help reveal place continuity: Iman referred to

an

actual traditional practice called paewuund kari (xix)

or glacier grafting as a more practical interpretation of

"mating" glaciers. Glacier grafting

involves growing a glacier. As far back as the twelfth century glaciers

were grown in villages in what is now known in northern Pakistan in

order

to block mountain passes that the Mongols would use to enter and invade

land. The practice of glacier grafting was invented by the people of

Baltistan. It involved dragging ice from a female glacier and a male

glacier, both pieces were planted at a specific site. Iman merged

place-lore with cultural practice in his conversation and provided an

antidote to maintaining place continuity. In doing so he highlighting

how

"the narrative potential of certain motifs of stories

may

be activated" when cultural heritage "

and in this case it is natural heritage" becomes

endangered. Belief narratives can also perform the same function. In

such

stories "Places also hold their inhabitants within

their

boundaries and order them protection, bringing people

together" (xxii) Wazir Iman narrated how a hunter in a

forest mistakenly shot a female ibex and the paris cursed him in

response.

He had murdered an animal that contained the ability to give life. Such

narratives reveal human misdeeds and the wrath of deities at upsetting

the

delicate balance that protects the environment.

My observations kept circling back to the dire environmental warnings

that

were inherent in the place-lore and imagination of inhabitants. Nearly

all

oral stories were underscored by an ominous realization: storytelling in

hill people is intertwined with a delicately woven web of nature related

materiality. Climate change could change the space and place

configurations of zomia and the zone that I have designated as pari

space.

Was it even a zone? Fluid, welcoming and imaginative as its constituents

were, it could not remain a "place" or

space for refuge if its ties to its muse were severed. The continuity

and

existence of pari space that contains genderless deities and shamanistic

practices rooted in transgressive acts (if we consider

nation states with their hegemonic narratives in

comparison)

were all tied to the recognition of the natural environment and a sense

of

place. Sense of place is a concept in heritage that allows for a lens

that

"integrates landscape and culture, the past and the

present, the movable and immovable, tangible and

intangible…" (xxiii) In this case the rituals and

storytelling help maintain the place distinctiveness, place continuity

and

an awareness of the self as a component in a much larger tapestry of

existence in Hunza. (xxiv, xxv)

Numerous ideas were percolating in my mind as I considered my initial

misgivings about understanding, challenging and imagining gender in

paris

as a mere tourist who was down se, the power of place-lore, the

fragility

of ecology and a general discomfort of state ideologies towards rituals

and practices that stray into nebulous territory. The image that emerged

from my reflection is an embodiment of this ambivalence.

(

Fig. 2) It is a

dialogue about home and identity: can we accept our multifaceted

historical pasts and acknowledge the imaginative potential of pari space

to foster a sense of place and respect for ecology? Or would the

supernatural storyworld appear as a threat to some?... an intractable

remnant from a bestial past that violates and defies dogma and societal

norms?

How, if at all, are artists from Hunza interpreting and acknowledging

these place-lore and ritual centric connections in their art? Back in

Lahore, I interviewed and analyzed the works of two graduates, Saima

Nagar

and Sajjad Roy who majored in miniature painting from the National

College

of Arts, Lahore. The visual strategies of both artists were unique.

Interestingly only one of the artists dabbled in attempts to borrow from

place-lore while the other also searched for inspiration through

possible

intra connections drawn from a pool of multi-ethnic ancestry and

transnational histories. Yet in one of their paintings both refer to a

common myth pertaining to the formation of Hunza; the visual

representations of both artists are distinct and ask questions about

identity and place in a world that sometimes privileges linear

histories,

borders and nation-states over varied historical imprints.

The myth that both artists collectively draw inspiration from is the

tale

of a cannibalistic king of Gilgit called Shirin Badad. As a ruler Shirin

Badad was cruel and unpopular amongst the people, he was known for

eating

babies. Legend has it that a kind prince from Baltistan secretly married

the daughter of Shirin Badad and had a son. Fearing that Shirin Badad

might harm the prince, she put him in a cradle and he floated across the

river until he was found by a woman washing clothes. Meanwhile a coup

was

plotted where Shirin Badad was killed. The prince was reunited with his

parents and became the king of Gilgit.

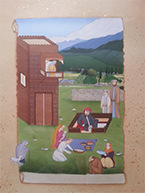

The triptych that Saima Ali shows me is part of her portfolio produced

as

an undergraduate student at NCA. Nagar opts to draw inspiration from the

Persian style of miniature painting. However, the landscape in the first

part has been painted directly from photographs and depicts the dramatic

mountain views of Hunza-Nagar. (Fig.

3)

Rather than opting for flat backgrounds or imaginary curling hilltops

often painted in multihued tones, Ali deliberately applies Eurocentric

conventions of painting such as atmospheric perspective where snowy

hilltops are bathed in hues of blue so as to represent recession of

space.

The foreground depicts a wooden building not too dissimilar to the ones

visible in traditional Persian miniature painting but Ali explains that

wooden architecture such as this is common in Hunza-Nagar. The scene

assumes we are familiar with the narrative: Shirin-Badad reclines

comfortably outside while villagers weep sorrowfully, aware that the

infant they are holding, swathed in a blanket will soon be devoured by

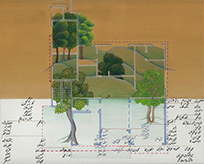

him. His daughter looks on helplessly from the balcony. The second part

of

the triptych shows a map in sepia tones that illustrates the prince from

Baltistan gazing longingly at Shirin Badad. Territory and geography are

used to define distance while in the lower corner the viewer encounters

them seeing off their child in a basket set to float down a river.

(Fig. 4) In this case, storytelling

through illustration serves as a means of underscoring the distinct

architecture, geography and natural landscape of the region. Fact and

fiction are meshed together, much like the tradition of storytelling in

the region and become conduits to celebrating sense of place of the

region

itself. It is worth mentioning that Saima Ali reflects on her own royal

lineage as well as she is a princess from the Kingdom of Nagar. Nagar

and

Hunza were once princely states that bordered each other. In 1974 these

states were dissolved and today Nagar is one of the ten districts in

Gilgit- Baltistan.

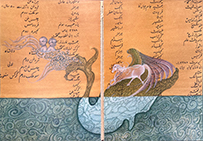

She acknowledges her transnational lineage through the paintings titled

Home Roots(Fig. 5) and Transcending

Borders. (Fig. 6) The background of

both

paintings features Ali’s genealogical family tree, she proudly explains

that many of the names mentioned are also used the in the celebrated

epic

poem of Iran called Shahnamah composed by Firdowsi in the tenth century

BC. Ali traces her family’s lineage from the last Sasanian King called

Yazdegerd. It is worth noting that both paintings feature natural

elements

such as land, water and trees. The tangible and intangible intermingle

to

serve as settings for the main story: Transcending Borders

(Fig. 6) illustrates a creation myth

of

Hunza-Nagar but pictorially also draws from the Shahnamah. The qualities

of the fabled mythical bird in Persian painting, the Simorgh who carries

a

future king Zal as a baby are used to narrate a creation story. The

painting depicts twin brothers who are born conjoined at birth emerging

from the sea separated, they emerge as Hunza and Nagar riding on the tip

of a hybrid creature that is composed of glaciers, ice and water. The

calculated use of ice, water, trees and hybrid demons questions the

cognitive process of merely observing everyday reality, recording

archives

and banal facts as we know it. This storyworld imbues these elements

with

the magical or as U lo and Daniel quote Basso who aptly

puts it by saying "When places are actively sensed, the

physical landscape becomes wedded to the landscape of the mind, to the

roving imagination…" (xxvi) Adopting the style of

Persian

miniature painting and using it to exaggerate, modify, stylize and

construct a whole imaginary world that exists outside time and space by

the artist is in sync with the spirit of tradition of miniature painting

which is wedded to the idea of constructing a third reality or liminal

space that exists between the heavens and the real world.

(xxvii)

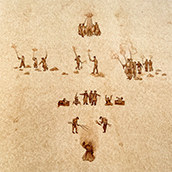

Interestingly Sajjad Roy opts for a more ethnographic approach to

framing

rituals and even storytelling. For instance, rather than the imaginary

storyworld Roy’s pictorial rendition of the tale of Shirin Badad is

presented through the use of the body and performance through the ritual

called Thumshaling. Roy pointedly states that Thumshaling is not

different

from burning effigies of Ravan on Dussehra . (xxviii)

An

effigy of Shirin Badat is burnt and people dance around a fire to

celebrate the end of his tyranny. An awareness of these connections on

Roy’s part demonstrates how stories, rituals and motifs are not just

connected to specific surroundings, but that their meanings accumulate

layer by layer, even invoking older religions and histories that add to

the multiplicity of cultural imprints. Perhaps that is why Roy’s

miniscule

figures outlined in brown pigment dance, play music and burn

Shirin-Badad

in the midst of a vast brown square of tea wash: (Fig.

7) The vast brown expanse is a canvas rooted in the

consciousness of a reciprocal relationship between land, storytelling

and

performative acts that narrate this connection. The colour of soil

informs

the colour of the figures. The more visceral and primordial aspect of

this

performance is also illustrated in another work (Fig.

8) where Thumshaling is depicted in the form of a more

subjective and sensory experience. Wavering shadows of dancing figures

and

embers of a campfire play off each other as one absorbs the untamed

landscape and multihued colours reflected across a night landscape.

In other works, Roy uses diptychs where the diagrammatic narration

through

tiny figures explains the ritual while the second part shows a more

personal connection with ritual.

Paintings such as Bitan (Fig. 9)

and Story of Bitan (Fig. 10) narrate

and

root these rituals almost in an ethnographic framework where the emotive

quality of the storyworld is rescinded in order to show the importance

of

the process. However, Roy revisits the same world and simultaneously

acknowledges it as a mysterious space where imagination and ties to

landscape can be recorded through intense, sensory experience such as in

his painting depicting a Bitan in ecstasy as he dances for the paris.

(Fig. 11) Raw, textured soil with its

many hues engulfs and compliments the scene. Once more the trance-like

psychedelic experience is exemplified by geography and landscape.

Both artists add to the rich cornucopia of what constitutes pari space

for

me; many of the acts and traditions appear to breach the frameworks laid

down by Reason, dogmas of faith and the State yet they also serve as

advisory warnings by addressing and entreating man to proceed with

caution

in this environment. The physical milieu of Hunza is defined by a desire

to pay homage to its distinct landscape through some form of creative

expression; these then reveal a web of meanings that inform lived

experiences and ensconce many worlds, little known histories.

An enduring relationship of fascination and " otherness

" when it comes to the observation and tabulation of

geography, particularly of hilly landscapes is visible even in the

memoirs

of travelers albeit in a more playful manner. In Al Qazvini’s memoirs of

medieval Iran he mentions an describes the mountain of Yaala Bashm

through

another eyewitness account. He says " One who climbed

the

mountain said to me: On it are images of creatures transformed by God

into

Stone. Among them is a shepherd leaning on a crook guarding his flock

and

a woman milking her cow, and other figures of human beings and beats.

" (xxix) As someone who was from down se I was

frequently

overwhelmed (Fig. 12) attributing them

with fantastical beings or imbuing them with magical qualities did not

seem all that unlikely after a number of treks and excursions to sites.

These examples illustrate the fact that the urge to record the

experience

of geography both in the form of a written account or even a photograph

is

tied to deeper urges; the landscape serves as muse, an object of wonder,

amusement and even awe. Place-lore has the capacity to emerge from this

wellspring of imagination.

These observations demonstrate how genius loci (xxx)

or

the spirit of a place carry stimuli that cement a unique bond with

landscape. Asad Bhai’s div at Ghizr then becomes a more tangible reality

and one can understand how genius loci may have even fueled Wazir Iman’s

evocative descriptions of glaciers as sentient or even romantic beings.

Sajjad Roy and Saima Nagar’s paintings then become archival documents

that

encode genealogies, myths and experiences in the form of ecological and

natural representations. Even living and working away from home, former

residents carry a fragment of this spirit in their creative impulses.

Unfortunately these worldviews are now under threat. Glacial melting is

accelerating every year. The International Community of Climate

Scientists

expects that 70% of the region’s glaciers could

disappear

by the turn of the century.(xxxi) As landslides, GLOFS

and other natural disasters perpetuated by climate change continue to

increase, the fate of these pockets of pari space spread across the

region, intertwined with community and life, hang in balance. This

unspoken fear now permeates everyday life across the region but

particularly in the north with its unique terrain. I remember one

unforgettable morning in Hunza where I froze midway as soon as a distant

rumbling of crumbling boulders silenced the valley of Gulkin. There was

a

pregnant pause. The birds could no longer be heard. In that what felt

like

the longest moment of overwhelming existential dread Asad Bhai scanned

the

expanse of the valley and cocked his ear to one side. Eventually his

characteristic sardonic wisdom kicked in as he looked up and said

"

these mountains and this dirt would have come down on

us by now if rain clouds had rumbled like this, bringing sheets of rain.

" Perhaps he had inadvertently voiced his greatest

fear.

(i) Sidky, M.H. “Shamans and

Mountain Spirits in “ Asian Folklore Studies 53, no.

1 (1994) : 78.

doi:https://www.jstor.org/stable/1178560.

Hunza

(ii) Scott, “ The Art of Not Being

Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia, The Art of Not

Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia,

“ p. ix,x.

(iii) I was introduced to James C Scott’s book by Saba

who discussed it extensively during our expedition noting that farming

methods, plot organization and other characteristics in Hunza are as

James

C Scott has described for hill people.

(iv) Jolly, Pieter. “ On the

Definition

of Shamanism. “ Current Anthropology, 04, 46, no. 1

( February 2005 ) : 127

(v) Indo-Aryan language spoken in the north of

Pakistan.

It is a Dardic language that does not have a long history of written

script

(vi) Murtaza, Zohreen. Interview with Mujeeb. Personal,

October 2022.

(vii) Harvest festival celebrated in Hunza-Nagar

(viii) Urdu word for plate

(ix) Murtaza, Zohreen. Interview with Sajjad Roy.

Personal, October 2022.

(x) Ibid.

(xi) Ibid.

(xii) Ibid.

(xiii) Murtaza, Zohreen. Interview with Asad Bhai.

Personal, September 2022.

(xiv) Vince “Adventures in the

Anthropocene,“, p. 54.

(xv) Murtaza, Zohreen. Interview with Wazir Iman.

Personal, September 2022.

(xvi) Ibid.

(xvii) Ibid.

(xviii) Valk Ülo and Sävborg Daniel, p. 9.

(xix) Murtaza, Zohreen. Interview with Wazir Iman. Personal, September 2022.

(xx) Vince “Adventures in the Anthropocene,“, p. 62.

(xxi) Amos, Dan Ben. “Asian Ethnology 79-1: Review *Theoretical

Milestones: Selected Writings of Lauri Honko* (Hakamies, Pekka and Anneli Honko, Eds. );

*the Theory of Culture of Folklorist Lauri Honko, 1932-2002: The Ecology of Tradition* (Kamppinen,

Matti and Pekka Hakamies).“ AE. Accessed February 5, 2023.

https://asianethnology.org/articles/2260.

(xxii) Valk Ülo and Sävborg Daniel, p. 8.tt

(xxiii) Hawke, “ 'Belonging: the Contribution of Heritage to Sense of

Place',“ p. 2.

(xxiv) Murtaza, Zohreen. Interview with Saima Nagar. Personal, November 2022.

(xxv) Dani, Ahmad Hasan, and Akbar Hussain Akbar. Essay. In Shah Rais Khan's History of Gilgit,

edited by Abdul Hamid Khawar, 5. Islamabad: Centre for the Study of the Civilizations of Central Asia,

Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad., 1987.

(xxvi) Valk Ülo and Sävborg Daniel, p. 8.

(xxvii) Nasr, “Islamic Art and Spirituality“, p.

(xxviii) A Hindu festival that celebrates the victory of Rama over the demon king Ravana who

abducted Ram’s wife, Sita. The event os commemorated by burning effigies of Ravana

(xxix)Kane, Bernard O'. “Rock Faces and Rock Figures in Persian Painting,“ n.d.

(xxix) Kane, Bernard O'. “Rock Faces and Rock Figures in

Persian Painting,“ n.d.

(xxx) Spirit of a place

(xxxi) Vince “Adventures in the Anthropocene,“, p. 53,54.

Bibliography

mos, Dan Ben. “Asian Ethnology 79-1: Review *Theoretical Milestones: Selected

Writings of Lauri Honko* (Hakamies, Pekka and Anneli Honko, Eds. ); *the Theory

of Culture of Folklorist Lauri Honko, 1932-2002: The Ecology of Tradition* (Kamppinen, Matti and

Pekka Hakamies). " AE. Accessed February 5, 2023.

https://asianethnology.org/articles/2260.

Dani, Ahmad Hasan, and Akbar Hussain Akbar. Essay. In Shah Rais Khan's History of Gilgit, edited by Abdul Hamid

Khawar, 5. Islamabad: Centre for the Study of the Civilizations of Central Asia, Quaid-i-Azam University,

Islamabad., 1987.

Hawke, Stephanie. In 'Belonging: the Contribution of Heritage to Sense of Place', 2, 2010.

Jolly, Pieter. “On the Definition of Shamanism.“ Current Anthropology, 04, 46,

no. 1 (February 2005): 127.

Kane, Bernard O' .“Rock Faces and Rock Figures in Persian Painting,“ n.d.

Murtaza, Zohreen. Interview with Wazir Iman. Personal, September 2022.

Murtaza, Zohreen. Interview with Asad Bhai. Personal, September 2022.

Murtaza, Zohreen. Interview with Sajjad Roy. Personal, October 2022.

Sidky, M.H. “Shamans and Mountain Spirits in Hunza.“ Asian Folklore Studies 53,

no. 1 (1994): 78. doi:https://www.jstor.org/stable/1178560.

Scott, James C. Preface. In The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia, ix,x.

New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2011.

Valk Ülo, and äSvborg Daniel. Essay. In Storied and Supernatural Places: Studies

in Spatial and Social Dimensions of Folklore and Sagas, 8. Helsinki: SKS, 2018.

Vince, Gaia. Essay. In Adventures in the Anthropocene, 54. London: Milkweed Editions, 2014.

Nasr, Hossein, Seyyed. Islamic Art and Spirituality. New York: State University of New York Press, 1987.