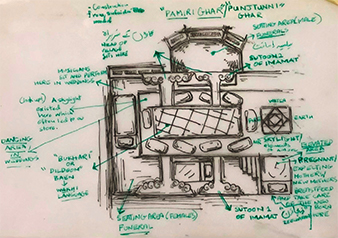

During our stay at Gulkin village in Hunza, Wazir Iman, a local farmer and specialist jam maker recounted the unique symbolism inherent in the design and construction of the cottage that the Pak Khawateen Painting Club had opted to stay at. The material of construction varied he said. Perhaps ages ago these cottages were constructed from juniper trees but today it is concrete and wood which is derived either from sheesham (Rosewood), diyaar (a type of pine) to safeda (poplar )Safeda is the most

common he said. Pieced together from memory, half-remembered phrases, conversations and a vivid description provided by Iman, the diagram of a portion of our cottage (Fig. 1), namely our main seating and bedding area provides insight into the relationship between lived spaces, ritual and aesthetics that are rooted in religion and even transnational encounters.

The windows on either side of the cottage consist of bay windows that

provide spectacular garden views that were set against a dramatic

landscape of the mountain valley. However, it is the entrance with its

large bay windows and alcove that prompt questions. Iman points to a

horizontal space at the top of one of the side walls at the entrance and

explains how either the Quran or a small chiragh,

lantern/candelabra use to be placed there

(Fig. 2). His descriptions of the design

of the main seating area are also embedded in a holistic understanding of

religion and rife with Shiite numerology/ symbolism. Iman

explains that "The five pillars

(sutoon) on either side of the main

seating area are synonymous with the panjtan (five

revered personages in Islam). The two larger ones denote

wahdaaniyat (oneness of God)which holds

precedence over all. These pillars are also associated with the Silsila of

Imamate (In Shite Islam certain individuals from the

lineage of Prophet Muhammad PBUH are included in this

chain). Exactly 72 beams are used to construct this

cottage in memory of the shuhadaa

(martyrs) who sacrificed their lives

with Hazrat Imam Hussain. The skylight in the seating area

(Fig. 3) denotes Nur(Divine

light of God) and possibly the four elements of nature:

air, water, fire, earth."

All activity in the main seating area takes place on the floor. The system

here is farshi (associated with the

ground/floor) Iman says and a low table with pillow

cushions occupies the central area. He uses the word Bukhari or Dildoom

Baen (in Wakhi language) to perhaps

refer to the large coverlet on which a dastarkhwan (buffet)

is rolled out at meals. It is worth noting that this seating style is very

common across the North and Northwest of Pakistan extending all the way to

West Asia.

Seating arrangements and segregation varies according to the occasion an

age. For instance, men are seated in or near the alcove during wedding

ceremonies and women are seated across the entrance during funerals.

Interestingly at the time of the nikah (wedding

engagement) the molvi(imam

who conducts the ceremony is also seated in the alcove while the head of

the village is seated against the pillar in accordance with the importance

accorded to its symbolism and association with religious belief. Pregnant

women and finally new mothers spend their first forty days in an elevated

portion of the seating area; the spatial arrangement not only emphasizes

the importance of their biological function which is the ability to

procreate and nurture but perhaps might also affirm and reinforce it as a

gift or attribute. Iman elaborates on another aspect stating that

protection of the new mothers is most important, hence their position in

that elevated corner.

The layout and design of the house, with its manifold rituals and

activities enables it to function as a living space, dynamic and open to

adaptation. It creates multiple realities, it is an embodiment of a

spiritual realm because its physical parts carry metaphors that allude to

the divine and sacred in accordance with Shiite belief, simultaneously it

shapes the way everyday life and cultural traditions are represented. The

house becomes a site for enacting a harmonious social organization during

all manner of events: birth, celebration and mourning. A complete circle

of life is performed in relation to the metaphors and symbolism of the

house thus retaining its Genius Loci. i.e "every being

has its Genius, its

guardian spirit. The spirit gives life to places and determines its

character. Thus within a space there are symbols and various intangible

features that differentiate it from another place."

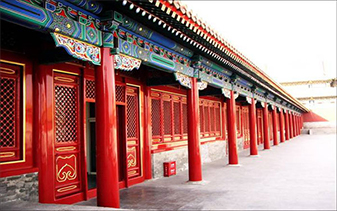

man explains that certain architectural facets and features of a home in

this region reveal ancient histories that stretch across time and

geography as well. For instance, he points to the pillars elaborating that

the pattern on the columns of the pillars is unique (

Fig. 4) because this

region was part of the Silk Route; travel and trade not only enabled an

exchange of goods but also of ideas. Although this is mere conjecture but

the scalloped design on the pillars is reminiscent of similar motifs that

are noticeable in many Buddhist temples. (Fig.

5) shows an image of a

pillar with a similar scalloped design at the Forbidden City in China.

Stylized forms of curling clouds similar to the ones carved into the

pillars at our Gulkin cottage were also painted onto the surface of such

temples. This transmission of aesthetics adds another facet to our

understanding of a home and its architecture as the embodiment of a living

heritage that is tied to its history, religion and

landscape.*

While some features are holistic, Iman feels that other modifications are

extraneous and arbitrary. He refers to the entrance alcove of the cottage

(Fig. 6) as one such example and is

slightly dismissive about it.

I recall seeing this architectural feature at a hill station that was

conceived and designed by the British, namely Murree. The image from

Murree shows an alcove of an estate mansion designed in colonial times

(Fig. 7) It shares similar

characteristics and juts out in much the same

way as our Gulkin cottage. Rather than embracing it with the same warmth

that Iman accords to the motifs on the pillars, Iman chooses to

"other"

this influence and calls it an imposition. Does this highlight an uneasy

relationship with a colonial past or simply

"outsiders" in general?

Unpacking facets of this simple dwelling reveals a constellation of ideas

all of which link architecture, tradition and even physical milieu. The

ownership and presence of both the architect and owner as active

participants in this close-knit community also becomes apparent, they are

nodes of a larger social unit in a cultural landscape that is deeply

entwined with its topography, territory and geography.

* Interpreting Vernacular Architecture in Asia, A Sense of Place,

Department of Architecture, University of Hong Kong, n.d.